Giant plate, known as 'OK', threw up coastal mountain range that created huge inland deserts, then sank into Pacific Ocean, study suggests

An ancient continent collided with East Asia and then, like the legendary island of Atlantis, disappeared into the ocean, according to a Chinese scientist.

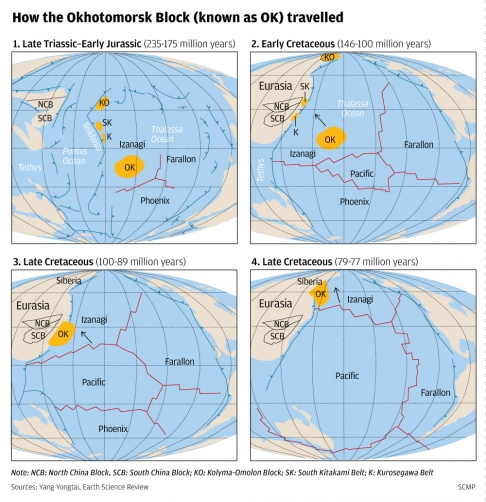

How the Okhotomorsk Block (known as OK) travelled. / Image from YANG Yongtai's group.

The collision created a mountain range up to 500 kilometres wide and more than 4,000 metres high along what is now coastal southern and eastern China. It also dramatically reshaped the landscape of Taiwan and other East Asian regions such as Japan.

But the continent was probably not Atlantis - the event happened about 100 million years ago, when dinosaurs still walked on the planet.

Writing in a leading earth sciences journal, Professor Yang Yongtai said the lost continent now lies below the Sea of Okhotsk in northeast Asia. It is known as the Okhotomorsk continental block, or simply "OK" to geologists.

A common belief in the field of tectonics - which concerns large-scale processes that affect the structure of the earth's crust - is that to the east of Asia there has never been anything but water. The expanding plate of the youthful Pacific had been constantly nudging the ancient plate of Eurasia to create the rugged landscape in East Asia, including the coastal mountains in China and volcanoes in Japan.

But in his paper in the latest issue of Earth-Science Reviews, Yang, of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Hefei , proposed there had been a continental collision in the region.

The OK was an old, hard and thick continental plate in the middle of the ancient ocean between Asia and America during the late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods.

Starting in the Early Cretaceous period, it gradually moved northwest with the birth and expansion of the Pacific plate, and about 100 million years ago the OK collided with the Eurasian plate in East Asia.

"We can still see clearly today the points of collision. In the south, a huge concavity [crater] can be found in southern Taiwan. In the north, there is a similar concavity in northeast Japan," Yang said.

"If you measure the distance between the two indenter corners you will find it matches almost perfectly the shape and size of the OK plate in Russia."

The collision lasted 11 million years.

In China, the push from the OK prompted the rise of Wuyi Mountain in Fujian , the Dalou Mountains in Yunnan , the Sichuan basin, the Dabie Mountains in Anhui , Hubei and Henan , the Qinling Mountain in Shaanxi , Yanshan Mountain in Beijing, the Luliang Mountains in Shanxi and the Ordos basin in Inner Mongolia .

The high mountains kept out the humid Pacific air, creating huge deserts and saltwater lakes in eastern China and Inner Mongolia during the late Cretaceous period.

"Such a dramatic change of landscape and climate must have brought a huge impact to all living creatures such as dinosaurs," Yang said. "The impact of OK on eastern China 100 million years ago was quite similar to the [impact of the] Indian plate on western China today. [The Indian plate] created mountain ranges like the Himalayas and deserts like those in Xinjiang . How dinosaurs could survive or thrive in such a harsh environment, I don't know."

About 89 million years ago, also due to the expansion of the Pacific, the OK began to move north along the Chinese coast and eventually collided with Siberia about 10 million years later.

Losing momentum, it gradually sank into the ocean.

Yang's new model could explain some famous geological mysteries in East Asia, such as the Sanbagawa metamorphic belt in Japan. The belt, stretching about 1,000 kilometres from Kyushu island through Tokyo and ending in Chiba prefecture, has left geologists scratching heads for decades. These rocks could only have been formed by extremely high pressure, requiring nearly twice the strength of the relatively gentle push of the oceanic Pacific plate.

Professor Sun Liguang, of the school of earth and space sciences at USTC, said he was a big fan of the new theory.

"For many, many years Chinese scientists have rarely contributed a big, original idea in earth science, so Yang's paper is very important," he said.

"We are troubled by many problems, such as the direction of major fault zones in the region, which cannot be solved by existing theories. Yang's model seems to hold the key for answers.

"Its impact will grow in the years to come," said Sun.

Cari Johnson, associate professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah in the United States, said Yang's theory was supported by regional literature. "This paper provides a synthesis of regional data to elucidate a 'new tectonic model' for the Pacific margin during the Late Cretaceous," she said. "It is a significant contribution."

But not all scientists are convinced. Professor Hu Xiumian, an associate professor in Nanjing University's department of earth sciences, said Yang's theory remained a wild guess due to the lack of key evidence.

"In southern China we have not found anything left behind by the OK. If such a big 'fight' did occur between the two continents, there should be some obvious marks for 'wounds'," he said.

Asahiko Taira, president of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, said Yang's theory needed more validation. "This is a very comprehensive … paper to try to explain the Cretaceous evolution of the eastern Asian margin, emphasising the importance of strike-slip tectonics. The model is worth further testing," he said.

South China Morning Post, 2013-10-27